As shelter-in-place orders wreaked havoc on businesses in cities and towns across the United States this summer, local leaders and their teams like Dan Henderson and the Gilbert Office of Economic Development had to make some fast decisions.

As director of the Office of Economic Development in Gilbert, Arizona, a community of more than 260,000 people southeast of Phoenix, Henderson’s team had heard from local brick-and-mortar and online entrepreneurs about plummeting revenue and skyrocketing debt from unpaid rent and overdue supplier bills.

“We engaged with 1,000-plus businesses,” says Henderson. “We knew they needed money to pay rent, leases and mortgages, their employees and to pay their extended family of vendors.”

Fortunately, in late May, Arizona Governor Doug Ducey allocated $441 million in federal CARES Act funds to cities and towns around the state. That included $29.2 million for Gilbert to use toward public safety and public health personnel expenses.

After healthy discussions about where best the money could be used, Gilbert’s Town Council chose to use the federal funds as directed. That then allowed them to reallocate the general fund budget, which would normally go to public safety and health, and use it to help local businesses confront the economic fallout from the pandemic.

What’s happening in Gilbert is playing out in cities, towns and counties across the country.

The pandemic has put enormous pressure on businesses of all sizes — whether they run a gift shop on Main Street, sell popsicles at local events or offer online web consulting. It’s also put pressure on policymakers who are searching for creative ways to shore up these contributors to their economic prosperity.

Related: Four policy pillars that will encourage online micro-businesses

“There are many things that make a strong community, but the first among equals is business,” says Gilbert’s town manager Patrick Banger. “Without businesses creating jobs, and those jobs creating revenues for people to pay their mortgages, send their kids to school, live their lives and provide funding for community services, what do we have? If we don’t have a healthy local economy, we’re not going to have a community.”

Of course, corporations and small businesses, which the Small Business Administration largely defines as companies with up to 500 employees, are a main driver of economic activity.

But researchers at UCLA Anderson Forecast, using Venture Forward data, have determined that micro businesses with just a handful of employees have an outsized impact on overall employment. According to the research, the existence of each everyday entrepreneur creates two more jobs in that community.

Gilbert’s approach to supporting its small businesses — including ones that only operate online — can serve as a model to other officials and policymakers grappling with the same issues.

The town relied on data and research, and tailored the program to meet what business owners said were their biggest needs. The town also built in accountability and metrics for success and for return on investment. In the process, Gilbert maintained the flexibility to adjust its approach as the pandemic persists.

Related: How Gilbert, Arizona, found economic resilience in 35,000 micro-businesses

Hard choices

When Gilbert’s CARES Act money arrived in early July, many officials saw it as an opportunity to upgrade critical facilities or build new ones. The town’s population is nearly 50 times as large as it was in 1980, which has put pressure on its emergency services, says Banger.

Prior to the pandemic, officials were already looking at three public safety capital projects, including a family advocacy center to help victims of sexual and domestic abuse, a backup Emergency Operations Center and expansions of the police dispatch center to handle an increasing number of calls.

“These were really worthy projects that we did at least throw up on the whiteboard for consideration,” says Banger.

At the same time, he says, the town’s policy makers and officials wanted a deeper understanding of “the extent and breadth of the need out there to help our businesses.”

To do that, the council set up a 13-person task force, which included members of the town council, fire and emergency services departments, the town attorney, and the budget director. As Economic Development director, Henderson then turned to a unique data set that would help the task force make its recommendations.

Data-driven decisions

Since 2018, GoDaddy has been working with academic research partners to evaluate the impact of its 20 million U.S. domain-name websites on the American economy and local communities.

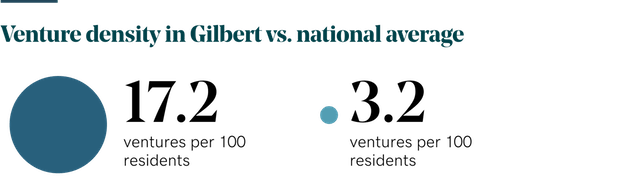

The multiyear research project, called Venture Forward, identified 35,000 online ventures in Gilbert. That makes it one of the most venture-dense places in the country, with 17.2 such entities for every 100 residents. (Nationally, the density rate is 3.2.)

Between creating jobs, generating revenue and spending on services, these micro-businesses contribute a lot to local economies. Venture Forward research has shown that adding one new highly active micro business — ones that contain many web links, generate significant traffic and contain features like payment portals — per 100 people boosts a county’s median household income by more than $400.

But because many of them don’t have a physical storefront or aren’t registered with the city, policymakers often overlook their impact.

To better understand how they could help nourish these ventures and encourage new ones, Henderson, along with then-Mayor Jenn Daniels, and their team worked with GoDaddy to survey Gilbert’s micro businesses.

The survey, conducted in February 2020 — before the crisis hit — among 226 GoDaddy customers there, found several key areas where Gilbert could take the lead in helping those businesses.

For instance, to start their micro businesses, respondents listed three main obstacles. Among them were marketing (48.8%), access to capital (28.3%) and permitting and licensing (27.7%). Once established, their concerns shifted, but only slightly. Marketing remained the top challenge (46%), followed by help finding skilled employees (19.6%) and then access to loans (17.8%).

Those data points, says Henderson, helped Gilbert’s task force assess business needs during the crisis. “That survey guided us tremendously,” he says. “It gave us a huge framework. It gave us what we called a pre-COVID understanding of business needs and wants. And then, using a similar survey and methodologies we went back to assess their current needs.”

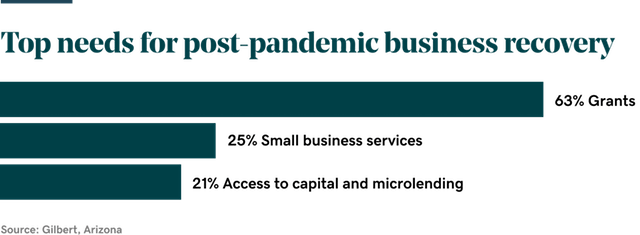

The results of Gilbert’s “business needs” survey, conducted in August, bore similarities to the previous one. Among businesses suffering from the impacts of the pandemic, 63% listed grants as the top need to help them with business recovery, with small business services next (25%) and access to capital and microlending (21%) in third place.

As for technical assistance, respondents again placed marketing as the top need (39%), putting it in a tie with customer acquisition. Social media training placed third (29%).

With that feedback, Henderson’s team was able to make data-driven recommendations to the task force. By late September, they had come up with a three-phase program that would use federal CARES Act dollars for highly targeted local solutions.

“We were able to use a data-driven approach to create a program to respond to a horrific set of events that businesses are still dealing with today,” says Henderson. “So we have a very replicable model and methodology and approach to taking data and information and public outreach and creating business solutions to solve real problems.”

The $18 million #GilbertTogether Business Recovery program that came out of that data-driven approach is designed to provide three things, says Henderson: “Immediate relief, sustainable recovery and long-term resilience for Gilbert businesses.”

Here’s how help works

Phase 1 provides $11 million in relief grants. Henderson calls this “the triage phase,” meant to alleviate financial hardship for businesses that had less than $5 million in gross revenue in 2019.

To qualify, a business must be able to show a revenue decline of at least 15% because of COVID-19. They can then receive a grant up to $35,000 based on their positive financial impact on Gilbert, which is determined based on things like payroll and capital investment.

The grant is being administered through a partnership with Arizona Community Foundation.

Phase 2 provides a total of $5 million in low-interest loans with Desert Financial Credit Union between $10,000 to $50,000. Its intent is to help businesses “consolidate their debts and give them some breathing room,” says Henderson. Loan recipients have up to 48 months to repay at 4% APR and up to 60 months at 5% APR with, in both cases, the first payment deferred for up to 90 days.

Phase 3 is a $2 million technical training and assistance program for business resilience.

These include assistance in areas such as customer acquisition, access to funding, social media support and marketing, which digital businesses often place at the top of their hierarchy of needs.

Online business training, coaching and marketing support will be provided through a partnership with local co-working space CO+HOOTS, Local First Arizona, Maricopa Community Colleges and Hownd, an automated promotions platform.

It also includes entry-level career training for residents provided by several community colleges in surrounding Maricopa County.

“We used data from both the GoDaddy survey and our own survey conducted in partnership with the Gilbert Chamber of Commerce to develop these programs, and that makes us unique among a lot of communities, and not just in Arizona,” says Henderson. “This type of data helps policymakers understand the needs of the business community, so they can make informed decisions.”

The same kind of support can help micro businesses elsewhere.

“Gilbert really is no different from the rest of the country in terms of what ventures have identified as needing help with,” says Karen Mossberger, an Arizona State University public affairs professor who has conducted the analysis for the Venture Forward study and who helped draft the initial Gilbert survey. “Marketing is always way above.”

In Gilbert, the task force is committed to quickly assessing whether their programs are working and, if it needs to, adjusting course. As businesses start to access the recovery programs, they are providing feedback on their experience, including businesses that may not initially qualify.

“We need to be able to iterate and expand the program to meet more needs,” says Henderson. “That’s what’s important to us. Meeting as many needs as we can and helping our businesses recover.”