Introduction

Last year, the GoDaddy Identity Platform began the journey to rethink how we enable authorization for users and services. Our design goals were to make sure the system we build is flexible for our future needs, centralized to enable better governance, and able to scale across the company. We decided to use OAuth 2.0 and OpenFGA for building this next-gen authorization system. This post will discuss why we adopted OpenFGA, some modeling challenges we faced, and how we use OAuth and OpenFGA together.

Why OAuth?

Our internal JWT claims-based authentication system has served us well and is not fundamentally all that different from OAuth. Both use JSON tokens with claims and signatures to authenticate a subject to a resource server. The key difference is that OAuth is a standard, and a standard that is widely adopted. This is beneficial for onboarding new developers, reducing engineer overhead, and making it easier to externalize our systems to third-party integrators.

OpenFGA - background and implementation at GoDaddy

OpenFGA is an open-source relationship-based access-control system based on concepts outlined in Google’s Zanzibar paper. The project's concepts documentation page is a great overview, but I’ll give a brief primer here.

In OpenFGA, an authorization question (a Check) is always of the form: “Does user U have relation R on object O?” The resolution of this question depends on two things: the authorization model and the relationship tuples stored in the system.

The authorization model defines the universe of possible types and their allowed relations. These relations can be direct (the relation edit_dns is defined on object type domain) or complex and indirect (the relation read_dns is defined on object type domain, and granted to any user who has the “read” relation on the domain folder that is the parent of this domain).

Relationship tuples are the persisted state of authorization relationships in the system. They are three-valued tuples consisting of a user, a relation, and an object:

{

"user": "customer:jacob",

"relation": "edit_dns",

"object": "domain:foo.com"

}We chose to adopt a relationship-based authorization system primarily because of its flexibility. The OpenFGA model allows us to build an authorization system that models simple service access, complex hierarchical policies, and role-based groups all together - something that would strain a pure role-based access-control system.

We chose OpenFGA specifically because of the project’s approach to database consistency and how that aligned with our operational experience and requirements. Much of the engineering complexity in Google’s Zanzibar system revolved around guaranteed consistency for authorization checks: clients can provide tokens that indicate the snapshot in time against which an authorization check must be made. These tokens (“zookies”) combined with the properties of Google’s Spanner database, allow for strong consistency guarantees when making authorization checks.

We decided that our systems could tolerate weak consistency and “incorrect” results due to cross-region writes and replication. OpenFGA’s operating model aligned with this policy, as did our operational experience: we lean heavily on DynamoDB global tables to distribute our services globally and make them resilient to regional outages. After a couple of months of writing a DynamoDB storage adapter for OpenFGA we had the system up and running.

Modeling global access

As we started to work through an authorization model for our early adopter internal systems, we ran into a modeling challenge: how do we handle global access to resources?

Consider the following toy authorization model for domains:

type user

type service

type domain

relations

define owner: [user]

define can_view_dns: [user, service] or owner

define can_edit_dns: [user, service] or ownerFine-grained permissions to view or edit DNS can be granted explicitly to a specific user or made available implicitly to the owner of the domain. Tuples like the following can be written:

< user:jacob, owner, domain:foo.com >

< user:bob, can_view_dns, domain:foo.com >And the domain service that owns editing DNS records can ask authorization questions:

// Can Jacob edit DNS for foo.com?

Check("user:jacob", "can_edit_dns", "domain:foo.com") -> resolves true

// Can Bob edit DNS for foo.com?

Check("user:bob", "can_edit_dns", "domain:foo.com") -> resolves falseThis works well if all access is fine-grained and limited to one or a few domains. But, say we have an internal service that must interact with the domain API to edit DNS outside the context of any particular user. What we would like to do is write a tuple that looks like:

< service:dns_updater, can_edit_dns, domain:* >With domain:* being a special wildcard object ID that indicates that it is true for any domain. This is unfortunately not possible in OpenFGA, so we had to find a different solution.

A key design goal we had was for each service to always make:

- exactly one

Checkcall for a given operation - the

Checkcall against a single relation for a given operation

We considered a few different approaches, but landed on one that utilizes some static global object IDs and OpenFGA’s contextual tuples feature. Contextual tuples are full tuples provided with a Check request that are then evaluated by the OpenFGA server as if they had been written to the store. To model global access, we extended our authorization model with the concept of “api types” (objects that represented an API). The following example illustrates how an API type can be used to grant global access to an object type:

type user

type service

type domain

relations

define domains_api: [domains_api]

define owner: [user]

define can_view_dns: [user, service] or owner or can_view_dns from domains_api

define can_edit_dns: [user, service] or owner or can_edit_dns from domains_api

type domains_api

relations

define can_view_dns: [service]

define can_edit_dns: [service]To actually grant global access, we use convention: all tuples written to domains_api are granted to a static global object ID:

< service:dns_updater, can_edit_dns, domains_api:global >The last missing piece is connecting a specific domain to the static global domains_api object. This is done using contextual tuples in the Check request. Here’s what that full Check request looks like for a service caller:

POST /check

{

"tuple_key": {

"user": "service:dns_updater",

"relation": "can_edit_dns",

"object": "domain:foo.com"

},

"contextual_tuples": {

"tuple_keys": [

{

"user": "domains_api:global",

"relation": "domains_api",

"object": "domain:foo.com"

}

]

}

}The contextual tuple is given with every request. With this approach, we’ve met our key goals without needing to write excessive tuples for every object entity in the system. The DNS API can always ask the same question: “Does this caller have the relation can_edit_dns on this specific domain?”. The power of OpenFGA and the centralized relationship-based model is that this question can be resolved in many different ways without the knowledge of the API owner. They simply ask the question and get an answer.

OAuth scopes, token claims, and OpenFGA

Now that we've covered fine-grained authorization with OpenFGA, let's discuss the other half of the equation: OAuth tokens and authorization. You may be wondering, OAuth is an authorization standard, why is a system like OpenFGA needed? To answer that in detail, I’ll refer you to a wonderful article by Vittorio Bertocci: On The Nature of OAuth2’s Scopes. The gist of it is, the scopes in an OAuth token only limit what an application can do on behalf of a subject. They do not (or should not, at least) convey any authorization information about the subject of the token or any requested resources. This is where a system like OpenFGA comes in. A resource server that accepts OAuth authentication must meet two criteria to ensure that the caller is properly authorized:

- The proper scope must be present in the token.

- A

Checkrequest must be made to OpenFGA for the subject of the token, the operation, and the requested resource. These are the OpenFGA user, relation, and object, respectively.

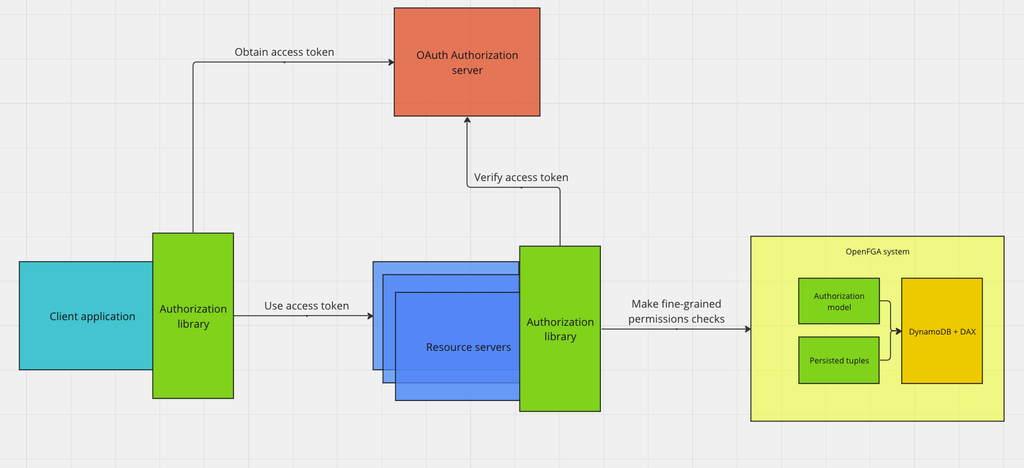

The following diagram illustrates how the entities in our system interact with each other:

The two-fold nature of this authorization policy implies some relationships between our OAuth claims, scopes, and the OpenFGA authorization model. We’ve taken a few steps to make this easier to manage and will continue to iterate as we deploy more broadly throughout the company.

First, we store metadata in our scope database that relates each scope to one or more OpenFGA types and relations. While there is one primary type and relation for a scope that will be checked by a service, there are other possible relations that may be written in different contexts. The global access use case is a good example. For our edit DNS operation on the domain system, we may define the scope domain.dns:edit. During normal operation, the domain service will check for that scope and make an authorization check against the main domain type: Check("service_dns_updater", "can_edit_dns", "domain:foo.com"). To grant global access for the domain.dns:edit operation, though, we’d write the tuple < service:dns_updater, can_edit_dns, domains_api:global >. Data on both of these relations is stored alongside the scope for use in client libraries and internal tooling.

Second, we structure the claims of our OAuth tokens to facilitate OpenFGA Check calls. Different OAuth grant types result in different types of IDs in the sub claim, and we don’t want service owners to need to distinguish between them when making authorization checks. So, the sub claim of tokens we issue are valid OpenFGA $user:$user_id strings, so they can be extracted and used directly in a Check API call without inspection.

Third, we are writing client libraries that expose a simplified authorization interface to API owners. As we’ve shown, there is some complexity in correctly authorizing an OAuth token. These libraries hide that complexity and let API owners focus on their business logic.

Conclusion

We are still at the start of our fine-grained authorization journey, but we are excited about the possibilities that OpenFGA and OAuth bring to our internal and external customers. Stay tuned for a follow-up blog post focused on OpenFGA performance and global scaling.