For the last five years, Dan Grech has been teaching entrepreneurs in Miami how to use the internet to grow their businesses. His clients are as eclectic as the city itself, ranging from long-established restaurants and hip new bakeries in need of a digital presence to boost online orders to first-timers like 14-year-old Zoe Terry, who created Zoe’s Dolls to give dolls of color to other Black girls like herself.

“Miami ranks as a leader in new business startups, but near the bottom in scale-ups,” says Grech, the founder and CEO of BizHack Academy. “We’ve always attracted dreamers and strivers, but we don’t have the technology ecosystem of other places, so a lot of people don’t have 21st-century skills for building new businesses. If we can close that gap, Miami will unleash a hurricane of innovation.”

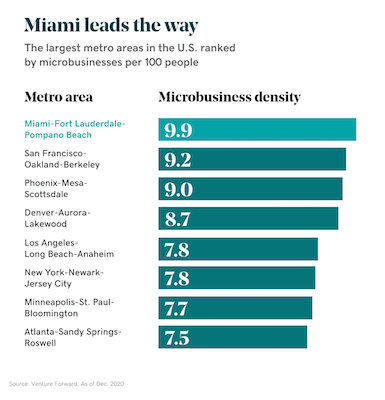

Therein lies the opportunity for Miami — and the challenge. The Miami metro area, including the nearby cities of Fort Lauderdale and Pompano Beach, has more digitally connected micro-businesses per person than any other major metro in the United States, with 9.9 per every 100 residents, according to Venture Forward, a multiyear research effort by GoDaddy to quantify the economic impact of micro-businesses.

In the city of Miami, the density is even higher, at 21.1 per 100 residents. And while the density of micro-businesses in some other high-concentration cities like San Francisco shrank in the latter half of 2020, it rose by 5 percent in Miami.

Online micro-businesses can make a big impact on local economies

These online micro-businesses, about half of which are run by “solopreneurs” and almost all of which have 10 or fewer employees, can make a big impact on local economies. Communities with greater density of micro-business have lower unemployment, higher household median income and are more resilient during economic downturns, data from Venture Forward shows.

Despite Miami’s high concentration of these types of businesses, the area faces special challenges to help its community of existing and aspiring micro-entrepreneurs.

While all businesses benefit from the region’s low tax rates and status as a hub of international commerce, Miami has a higher percentage of “startups of survival,” which are born out of necessity rather than opportunity, than other cities, according to a survey from the Kauffman Foundation.

Many of these are owned by immigrants from Central and South America, who are more concerned with paying the bills than chasing big, new markets, and are vulnerable to sudden shifts in the economy.

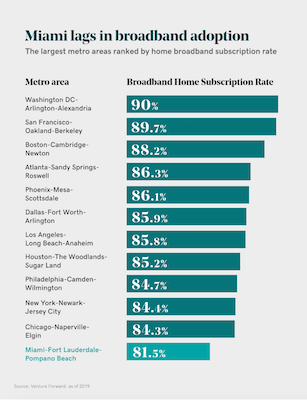

And other would-be entrepreneurs have been stifled by problems such as spotty broadband distribution. Miami ranks last among major metropolitan areas in-home broadband adoption, with many low-income residents, in particular, lacking the connections required to run and access online businesses, according to Venture Forward. The problem is especially pronounced in predominantly Black neighborhoods.

Supporting startups big and small

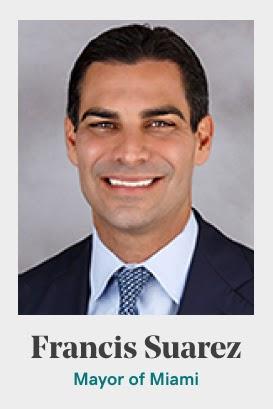

Miami’s leaders are aware of these problems. In mid-March, Mayor Francis X. Suarez announced Miami Connected, a partnership with private investors, government and civic groups to provide broadband access and digital literacy training to public schools in low-income neighborhoods, starting with the mostly Black neighborhoods of Overtown and Homestead.

And in February, Miami-Dade County Mayor Daniella Levine Cava announced a program called Renew305 that includes $1.5 million in grants to provide new skills, a revolving loan fund for small businesses called RISE Miami-Dade, and an Office of Equity and Inclusion.

The moves will “make sure minority- and women-owned businesses get a share of the pie and ensure we help businesses in every community start-up and grow,” she told the South Florida Business Journal.

At the same time, Mayor Suarez is aggressively courting tech companies, trying to get them to relocate from higher-cost, higher-stress cities.

Suarez has vowed to make Miami the first city to accept bitcoin as a form of payment for government services, holds periodic “Cafecito Talks” with tech entrepreneurs and investors on Twitter, and is quoted on a billboard in downtown San Francisco saying, “Thinking about moving to Miami? DM me.” The payoff for these efforts could be significant, as the work-from-anywhere policies prompted by the pandemic have created a once-in-a-generation opportunity to woo companies to the area.

Yet academics and community leaders warn that it will take concerted, sustained effort to satisfy the needs of well-funded tech companies without neglecting those of micro-businesses.

While economic development professionals around the country understandably prioritize efforts to lure big employers, they often miss the importance, both economic and cultural, of their smallest homegrown startups, says Peter Roberts, a professor of organization and management at Emory University who has studied micro-businesses for many years.

For example, Miami’s Cuban “Cafecito” joints serving sweet Cuban espressos not only provide jobs and add to the tax base, but also increase commerce in the neighborhood and are a reason people visit and sometimes stay in the city.

“I’m not disparaging efforts to attract larger companies, but the tendency is for policymakers not to take micro-businesses as seriously,” Roberts says. His research suggests that cities that are successful in attracting big corporations end up displacing instead of serving the people who live in those communities. “Sometimes the right answer is to help 1,000 companies hire five people, rather than help one hire 5,000.”

There are other challenges for policymakers, too. Many micro-businesses take a while to register officially, or never do, so they don’t show up in studies and reports. Some are side hustles that generate income for their owners, but haven’t yet developed into full-time efforts.

Consider Natasha Williams. A longtime Miami tap dance teacher and performer, Williams saw most of her work dry up when the pandemic started. That’s when she decided to capitalize on her flair for style to launch Natasha Nails, which sells hand-painted press-on nails. While her online store, buoyed by an Instagram account with more than 5,000 followers, is bringing just a few hundred dollars a month, she’s convinced of its potential.

“I want the business to grow big, until we’re selling at Target,” says Williams, who hasn’t yet registered the business. “But everything is a step at a time.”

The power of inclusive broadband

Some community activists agree that without thoughtful public policy to help micro-businesses like Williams’, an influx of tech companies and their often affluent workers could exacerbate problems such as gentrification and hurt a critical part of Miami’s economy.

“It’s great that we’re trying to attract tech companies because tech is the future,” says Mileyka Burgos-Flores, executive director of The Allapattah Collaborative, which helped small businesses in that low-income, heavily Dominican neighborhood raise $700,000 in grants, loans and other resources in 2020. “But we’ve all heard about what’s happened in San Francisco and Austin and Seattle, where the success of tech has made inequities far worse.”

Perhaps the most obvious precursor to giving local entrepreneurial communities a boost is by making broadband more widely available and affordable, says Karen Mossberger, a professor of public policy and community solutions at Arizona State University.

But new research from Venture Forward shows that the broadband plumbing alone, while necessary for supporting micro-businesses, is not sufficient to reduce unemployment.

It’s only when citizens tap that broadband to build micro-businesses — rather than just watch Netflix and play games, for example — that there is a meaningful economic impact.

The Venture Forward data shows that the combination of widespread broadband and a high density of micro-businesses brings unemployment down.

According to Mossberger, communities that added five more ventures per 100 people and had high broadband connectivity could reduce unemployment rates by 2 percentage points on average. This is a significant difference, given that during the worst of the economic fallout from the pandemic last April, unemployment was 14.4 percent for the nation as a whole.

“Inclusive broadband lays the groundwork for a culture of innovation that benefits everyone,” Mossberger says. “Making sure everyone has access to broadband is one of the best ways to generate the most benefit for the local community.”

Uneven distribution and vulnerabilities in micro-businesses

There are many explanations for Miami’s abundance of micro-businesses, from a relative lack of large corporate employers to an abundance of enterprising immigrants. But entrepreneurship is equally distributed.

For example, zip codes with predominantly Black residents had 55% fewer small businesses in 2018 than other parts of the city, says Emory’s Roberts.

ASU’s Mossberger says expanding access to affordable broadband is a must if this disparity is going to be addressed. At a time when the ability to advertise online and take digital orders is more critical than ever, only 56% of Black residents of Miami have adequate broadband, compared to 72% of Latinx residents and 88% of whites, she says. In mostly Black enclaves such as Liberty City, it can even be hard to get a decent cell phone connection, says Elaine Black, CEO of the Liberty City Trust, which lends to local businesses. “Don’t be surprised if we lose this line in the next few minutes,” she warned a reporter during a recent call.

Other factors suggest that Miami’s micro-business community, while vibrant, remains fragile.

Miami’s numerous “startups of survival” were created by people who are fighting just to pay their bills, not chasing a big payday. Many are immigrants, who have few cash reserves and are not aware of, or are unable to tap, government assistance programs.

“Almost every business gets its seed money from friends and family,” says Grech. “But a lot of these people were totally on their own.”

How to help Miami’s micro-businesses

So what can Miami’s policymakers do — besides making broadband more accessible — to help? According to Venture Forward surveys of thousands of founders who use GoDaddy’s website-building tools, the top request micro-businesses have for local governments is help with digital marketing, so they can navigate the bewildering world of advertising on Facebook and Instagram and getting their websites ranked prominently on Google or Yelp.

While there’s a thriving cottage industry of consultants offering digital marketing coaching, Grech found that too few are focused on helping the least sophisticated business owners. “It’s where the need is greatest and the availability of services is weakest,” he says.

Data from Empower, a GoDaddy program that provides coursework and financial support for community groups that provide training to underserved communities, backs up Grech’s point. Many of the 1,756 entrepreneurs surveyed by Empower in 2020 needed basic digital literacy training to take the courses, and 79% needed hands-on support to actually set up a website.

When made available, the results can be transformational.

In spite of COVID-19, 40% of Empower participants reported an increase in revenue in 2020. Grech, for example, tells of a woman who ran a struggling daycare service in the mostly Black, low-income city of Opa-Locka just north of Miami. After she posted her first ads on Facebook and Instagram, a daily investment of just $15, she added clients that should bring in $64,000 of extra revenue in coming years.

But many of Miami’s micro-entrepreneurs, particularly recent immigrants, need even more rudimentary help. “A lot of these people don’t even know how to use their phones, and they don’t have time to learn,” says Burgos-Flores, whose Allapattah Collaborative provides workshops, classes and one-on-one coaching. “You’re not going to get someone to go from keeping receipts in a shoebox to using QuickBooks and Slack overnight. You’ve got to meet them where they are.”

Closing the information gap

Sometimes, that means literally meeting them where they are. When Burgos-Flores heard in February that the U.S. government was extending its Payroll Protection Program to micro-businesses with no employees, she immediately organized a team of canvassers to go door-to-door to spread the word through Allapattah. The aid could have an outsized impact in the neighborhood, which has suffered soaring unemployment and widespread closures due to the pandemic.

“Most of these people are not digitally connected, and I’ll tell you the truth: 90% of them are skeptical that anyone is going to come to their door offering free money,” says Burgos-Flores. “But a few asked for more information. It’s a step in the right direction.”

Spreading the word more widely about available assistance programs could go a long way toward strengthening Miami’s smallest businesses. In one survey of the city of North Miami, 92 percent of micro-business owners hadn’t received any technical help, and all of those that did got it from friends and family, says Ahmed Mori, vice president of economic development for Catalyst Miami, a group founded by Miami-Dade’s Levine-Cava in 1996 to help the city’s poorer residents.

“Not one small business reported any help from a nonprofit technical assistance provider,” he says. “None of them even knew free technical assistance existed.”

Striking the right balance for new business in Miami

Many advocates for Miami’s micro-businesses praise Mayor Suarez’s push to attract Silicon Valley–style tech firms. While it won’t turn the area into a major tech hub overnight — Southeast Florida still ranks 37th out of the top 50 top markets for tech jobs, according to a recent survey — it’s likely to bring benefits that could ripple across the economy.

But the micro-businesses that have helped make Miami the unique place it is, deserves attention too, says Burgos-Flores.

“The problem really isn’t bad policies, it’s a lack of policies that help small businesses thrive,” she says. Investing in the success of micro-entrepreneurs could even help make Miami more enticing for the very tech businesses the city hopes to lure. “Otherwise, it’d be like building a house to take the best care of your guests, rather than your children,” she says.