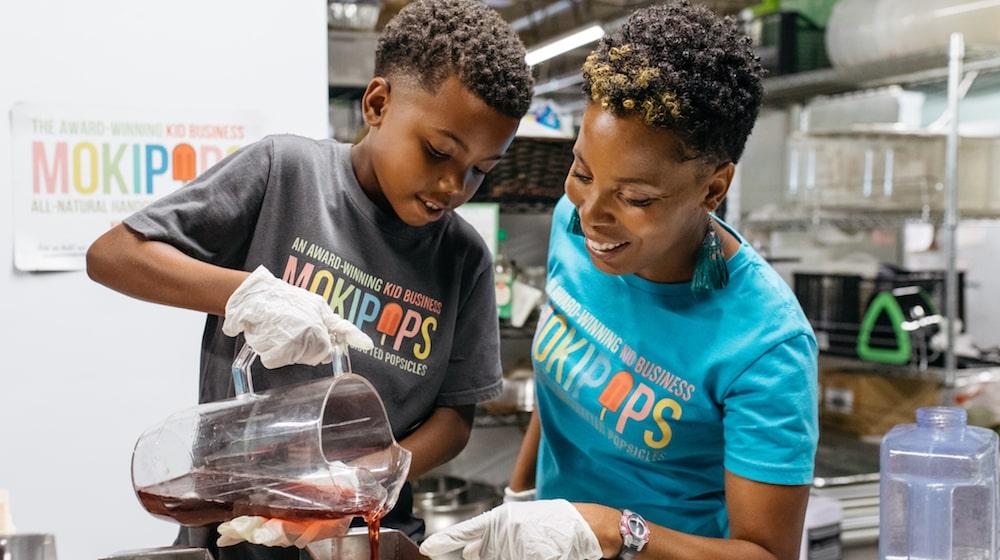

Amber Khan-Robinson, the daughter of the first African American athletic shoe designer in the U.S., has always had entrepreneurship in her blood. So when she was looking for ways to keep her three children from staring at screens all day, she decided to help them “start a business.”

Working at home in Atlanta, they made 85 hibiscus lime ice pops to sell at a festival. Soon, the family was selling hundreds per weekend at events around their city under the name MOKIPOPS.

When the pandemic hit, MOKIPOPS, like many neighborhood businesses, was forced to pivot their business to maintain sales. So Khan-Robinson set up a website for online orders. As customers began ticking up, the whole family pulled together to keep MOKIPOPS afloat.

“We just started delivering,” Khan-Robinson says.

She and her husband drive their 10-year-old son to a customer’s address and he takes it from there.

“He runs up, rings the doorbell with his mask on, and leaves it at the door,” she says.

The next step for her budding ecommerce operation? Figuring out how to ship orders in a cost-effective way, which Khan-Robinson calls “a daunting task.”

MOKIPOPS is one of the millions of internet-enabled micro-businesses in the United States.

These businesses, which are often overlooked by traditional economic surveys, create jobs, reduce unemployment, and boost median household income, according to data from Venture Forward, a multiyear initiative that looks at the economic impact of 20 million websites registered with GoDaddy.

This year, they’ve also helped blunt the economic toll of the pandemic.

More diversity, more micro-businesses

New data from Venture Forward shows that diverse communities are primed to gain the most from these micro-businesses.

Cities and neighborhoods with a higher percentage of foreign-born, African American and Hispanic residents — like Atlanta, where more than half the population is African American — tend to have more micro-businesses per 100 people than less diverse ones.

And while micro-businesses often represent a supplemental source of income for their owners, minority entrepreneurs are more likely to want to turn them into their main employment, according to a 2,330-person survey conducted by GoDaddy.

The upshot: micro-businesses have the potential to make a positive impact in minority communities, even as they’ve been hit harder than most by the pandemic, both economically and from a public health perspective.

“We should have a more comprehensive policy about how to support small businesses, and particularly small businesses owned by people of color, Asians and other groups that have been marginalized,” says Connie E. Evans, president and CEO of the Association for Enterprise Opportunity (AEO), which champions underserved businesses across the country.

Indeed, civic leaders who take steps to harness the potential of micro-businesses can help to revive their local economies.

Related: Online micro-businesses can be an easy economic win for local governments

There are “inequities that exist across racial divides in general, but in entrepreneurship specifically,” says Stacy Cline, senior director of corporate social responsibility and sustainability at GoDaddy, who spearheads Empower, a philanthropic program designed to support entrepreneurship in underserved communities.

By providing these people with the skills required to build their own businesses, “they can provide for their families and they can give back to their community,” she says.

Moving online because of the pandemic

Consuelo Rosales has worked hard to overcome those inequities.

An immigrant from Mexico and mother of three who lives in Jonesboro, Arkansas, and works in nearby Memphis, Tennessee, she spent a decade as a housekeeper. After splitting from an abusive husband three years ago, she started Consuelo’s Cleaning Services, relying on support from a community organization that helped her with basic business skills.

By early 2020, Rosales had three employees and an office and was making enough to provide for her children.

Then the pandemic hit, customers vanished and she had to lay off her employees. Her preferred way of finding new customers — knocking on doors — was out of the question.

With the help of the same community organization, the Georgia Micro Enterprise Network, Rosales was able to set up a website.

By June, she began to get calls from new customers who found her online. First, a restaurant she had worked with before, then a homeowner.

A few months later, Consuelo’s Cleaning Services has around 30 residential customers and six commercial ones — and seven employees. Roughly two-thirds of her new business is from people who find her online and the remainder from referrals.

“I was on the verge of giving up,” Rosales says. “With the pandemic, I couldn’t go knocking on doors. People weren’t going to open. Going online was my only recourse.”

Rosales’ determination and drive are hardly unique. GoDaddy’s survey found that 66% of micro-business owners say their website has helped them adapt during COVID-19.

And while about 2 out of every 5 respondents consider themselves fully employed by their micro-business, many of those who don’t would like to be — turning what’s essentially a side hustle into a main source of income.

From side hustle to main employment

The survey found that the desire to turn ventures into full-time jobs is especially true among micro-entrepreneurs who are African American, women and foreign-born.

African American survey respondents are 27% more likely than others to rely on their micro-business as supplemental income and 2.5 times more likely to want to turn the venture into their main source of income.

Women are 36% more likely than men to rely on their micro-business as supplemental income and 68% more likely to want to turn the venture into their main source of income.

Foreign-born micro-entrepreneurs are 1.5 times more likely to want to convert their venture’s supplemental income to main income.

Turning those entrepreneurial ambitions into reality often requires help.

Skills training, access to capital, flexible benefits and access to broadband have all been shown to foster growth in micro-businesses.

Community organizations like the ones that helped Rosales, are playing a growing role in helping foreign and minority entrepreneurs.

But policymakers can also make a major difference. The new data from Venture Forward, for example, highlights a subtle but important variable that a policymaker could focus on — internet connectivity.

Related: Four policy pillars that will encourage online micro-businesses

Inclusive broadband fuels entrepreneurship and employment

To maximize the economic jolt from micro-businesses, broadband not only should be available but also utilized.

For instance, while higher poverty rates generally lead to a lower concentration of micro-businesses, more broadband adoption in poorer communities can offset that deficit and result in a higher concentration of ventures.

And since the start of the pandemic in March, Venture Forward data shows communities of all income levels with a 75% or higher broadband-adoption rate would see unemployment decrease for every micro-business per 100 people they add.

“This pandemic has disproportionately impacted communities of color,” says Larry Irving, former head of the National Telecommunications Infrastructure Administration who helped prove the existence of a digital divide.

“It's disproportionately impacted low-income wage earners. It’s disproportionately closed small businesses owned in low-income and rural communities, and the ones owned by women. Broadband gives the opportunity for those businesses to come back, to expand their reach, to find creative ways of doing business.”

The impact of inclusive broadband has only deepened with the pandemic.

A large percentage of African-American-owned businesses like restaurants and personal services used to exist strictly in the brick-and-mortar world.

“Now we’re seeing lots and lots of people pivoting” to online, Evans, of the AEO, says. “It’s a necessity to have a digital presence. The world is digital.”

Affordable broadband isn’t just important to get a micro-business online. It has to be widespread in the surrounding community or the micro-business won’t have any customers.

“We should be having more of a policy argument about how to create more broadband assets to help micro-businesses,” says William Yu, an economist at the UCLA Anderson School of Management and its Anderson Forecast team. “That’s the right direction for the 21st century.”

For Rosales, connectivity came just in time.

“I could never have reached this many customers without it,” she said. “It’s allowed me to support myself and to hire seven people. It also makes us look more professional. So it not only saved my business, but also made it better.”

Related: Download the Fall 2020 Venture Forward report